Methodology

Contents

Methodology#

Developing and maintaining open source software relies on an integration of technical, social and organisational factors. A mixed methods study was therefore designed to understand all aspects of this sociotechnological system. We collected quantitative and qualitative data concurrently and used one source’s findings as cross-validation for the other. Thousands of projects were analysed across six dimensions:

General overview - project themes, growth, age and popularity, and general project maturity.

Technology - preferred programming languages, licence use, and technical challenges facing contributors.

Community - community composition and participation, and overall activity.

Ecosystem collaborations - cooperation across and within sectors and disciplines.

Financial sustainability - business models and funding mechanisms.

Quantitative Analysis#

From October 2020 until August 2022, ~1300 actively developed open source projects were crowdsourced and curated. All entries were selected based on the contribution guide of OpenSustain.tech. For a project to be listed, it must:

Follow at least one aspect of the Open Sustainability Principles.

Be instrumental to the preservation and restoration of natural ecosystems, support climate change mitigation or adaptation, or enable environmental sustainability more broadly, through open technology, methods, data, knowledge, intelligence or tools.

Be used by others outside the core project or organisation.

Be structured and documented in a way that allows maintenance, reuse and extendability.

Be published under an open source licence.

The project dataset is entirely machine-generated based on data from OpenSustain.tech and metadata from the GitHub API. Due to the limitation of the database, we assume that a project takes place in a single repository. If multiple repositories could be identified as belonging to a single project, the main repository was identified and listed. For this reason, the terms repository and project are used analogously in this study. When entering the projects, care was taken to use the main repository of a project. The methodology and code used to parse and analyse the data are available in the AwesomeCure repository. The scripts for generating the plots can be found in the repository of the study. Several strategies were tested to include as many projects as possible in data collection using multiple keywords related to sustainable technology and environmental sustainability:

Searching OSS platforms like Gitlab, GitHub, Bitbucket or Zenodo.

Mining scientific papers for terms like git, and searching in each paper’s keyword dictionary.

Using search engines for OSS, such as Libraries.io, PyPi or rdrr.io.

Investigating OSS related journals such as the Journal of Open Source Software.

Crowdsourcing input, and interviewing people working in relevant domains.

Browsing stars awarded by developers.

Despite extensive research and a comprehensive use of complementary strategies, this database is only representative of a subset of projects within this domain, and should therefore not be considered exhaustive. We must acknowledge that several technological developments relevant to OSS in environmental sustainability which are not directly related to outcomes in environmental sustainability. Instead, they provide the technical foundation that enables this software. The lines here are frequently blurred, and the extent to which a development contributes to environmental sustainability is difficult to predict. For example, a geoscience development that contributes to the exploitation of oil fields could also contribute to the exploitation of geothermal energy.

Furthermore, some important attributes, such as the number of clones and downloads could not be collected via the GitHub API. Projects on self-hosted Git platforms are also more difficult to find. While not currently supported, future re-analysis will consider other platforms, such as GitLab, more extensively. The number of open projects which reuse an open source software project is another important attribute. We were able to obtain this data for Python projects via GitHub using a web crawler. Other data, such as user permissions, cannot be viewed in individual projects without additional authorisation. For this reason, governance structures in most open source projects are difficult to determine. Individuals who did not contribute code were excluded from our analyses. Even if such contributions are critical, they cannot be obtained through the GitHub API at this time.

Development Distribution Score#

In this study, a proxy is developed to quantify the Bus Factor, the Development Distribution Score (DDS). The DDS weighs how the development is distributed between project contributors by benchmarking the individual with the most commits in relation to the other developers. DDS seeks to measure how distributed the knowledge, work, and governance is in relation to other projects. The metric compares a project’s reliance on a small group of contributors and, therefore, its resilience to change. It can be seen as a lead indicator of health and complexity, whereby the greater the diversity of knowledge accumulated and distributed in a community, the greater the community’s resilience and productive capabilities. More details about this can be found in chapter Development Distribution Score.

Qualitative Analysis#

OSS communities are keystone actors of OSS projects. They are typically initiated by an individuals or groups with specific needs often not met by existing solutions. We conducted 15 interviews with developers and contributors from projects of various sizes and fields, including environmental economics, sustainable finance, climate and earth science, energy system modelling, renewable energy, batteries and transportation. Because we used a concurrent rather than sequential triangulation strategy, we had the opportunity to revisit and enhance our model to account for information revealed by the interviews. We drew inspiration from the questions asked in Roadwork ahead to enquire about the developers’ challenges, incentives, needs, the financial viability of their projects, and the barriers that have hampered the development of best practices. We asked about:

Trajectories and positions in OSS – What are you working on, and how did you end up there? Where do you see your project related to the broader open sustainable ecosystem?

Technology & support - What open datasets and tools are you missing? What do you need to maintain your project in the near term?

Community - How many users does your project have, and how is this metric tracked? What efforts are made to build a diverse developer base? What is the developer model? How are developers retained?

Collaboration - In which field would you like to see more collaboration?

Financial sustainability - What efforts are being made to reach your definition of sustainability? What are your sources of funding or sponsorship?

Future outlook - Do you see your project being widely used by your community in the future? What are the top 5 open sustainable projects on your radar?

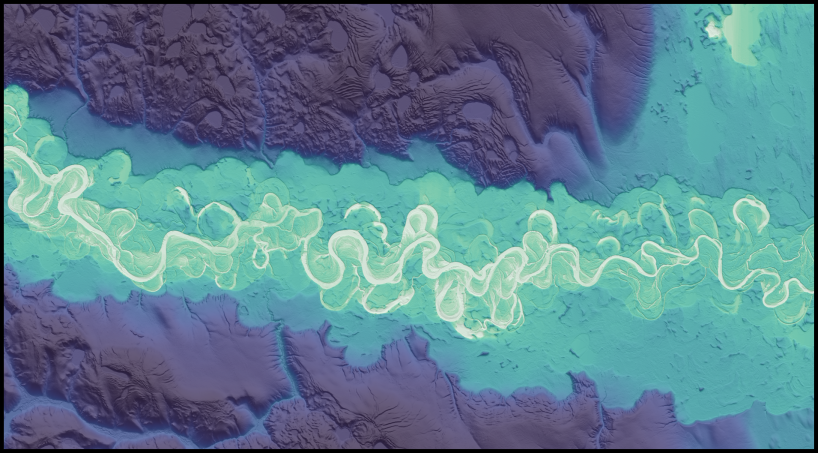

Fig. 7 - Beaver Creek, a tributary to the Yukon River, Alaska, USA. Visualisation created with the open source Python package RiverREM. License: GPL-3.0#